Artemisia Gentileschi

It seems right to us to dedicate the first article of this blog to one of our inspiring muses… painter, wife, mother, lover and great warrior, Artemisia Gentileschi is an icon symbol of feminism, a woman who rebelled against rape immediately by bringing her executioner to court. But throughout his life he was at the center of controversy and gossip.

Her life was marked by a terrible drama, a rape, but also by a deserved success as a painter. Born in Rome in 1593, she was the daughter of Orazio Gentileschi, painter of the time and friend of Caravaggio. The young woman embarks on her father’s career, attends artists and paints sublime, and Horace goes out of his way to spread his art, telling and writing to the most influential characters of his daughter’s talent.

Motherless, she approaches Tuzia who enters the Gentileschi house and becomes an inseparable friend of Artemisia. At only 17 years old he made the first painting “Susanna and the Elders”, where you can see the realism of Caravaggio and the shapes of the Carracci. Artemisia Gentileschi’s life and success are clouded by a terrible scandal that deeply marks her life and her art. Despite the father’s letters of recommendation, the young painter had not been admitted to painting studies, and had therefore started taking perspective lessons from Tassi. Although the girl was confined in the house by her father, Agostino Tassi, painter and friend of her father, manages to take advantage of her with Tuzia’s complacency and despite Artemisia’s firm refusals.

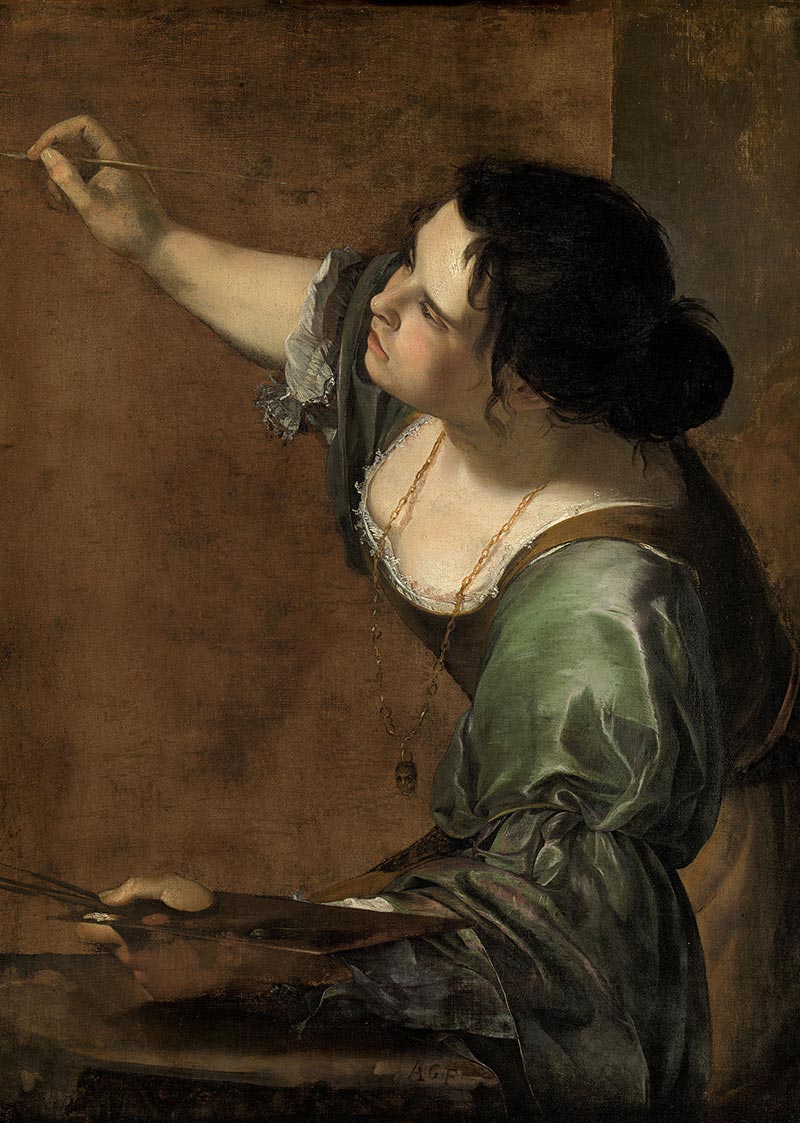

Artemisia's self-portrait as an allegory of Painting (1638-1639)

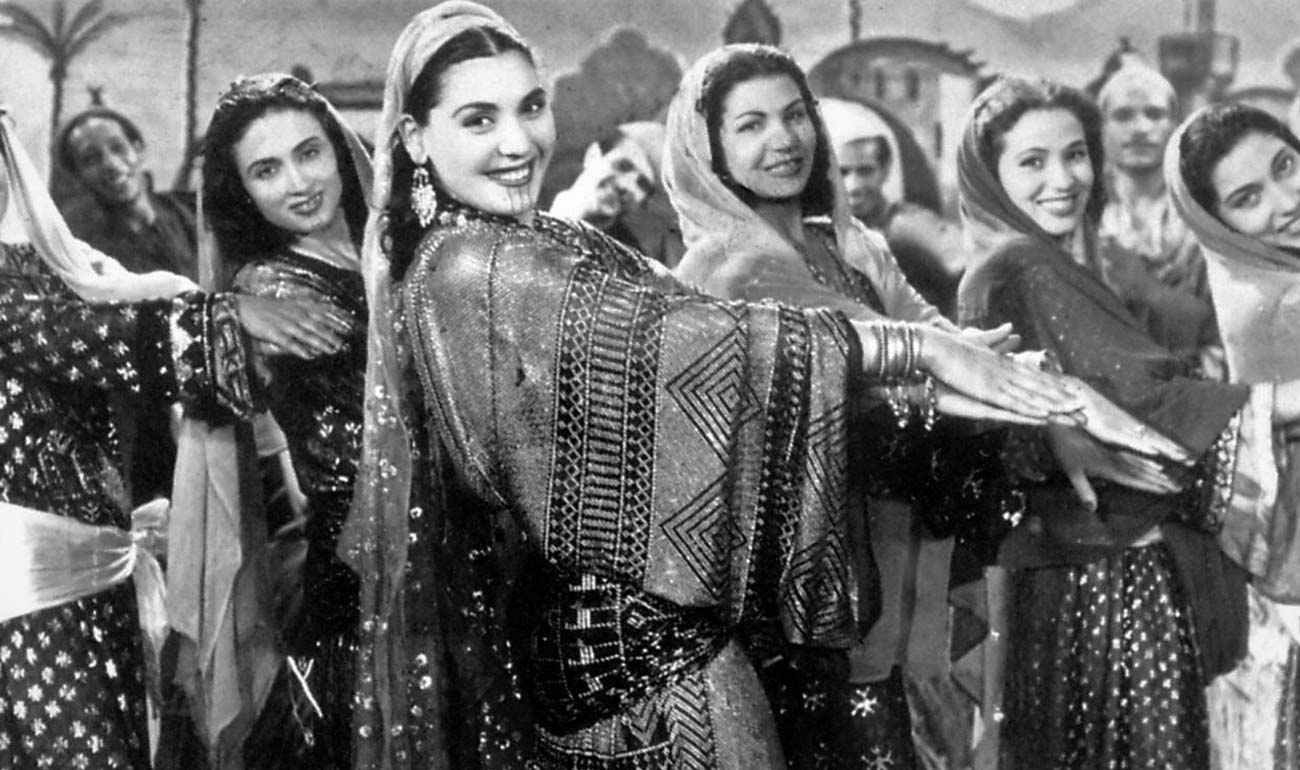

Judith and her maid (1618-1619)

THE RAPE

The girl is raped at 18. Horace reports the fact to the authorities after about a year. A rape trial, at the time, marks Artemisia’s dishonor that from that moment on, despite being a victim, she is considered a little good.

At the trial there is talk of reparatory marriage, but Tassi is already married. The story, however, remains unclear: Horace also asks for compensation for the theft of some of his paintings. Throughout this story, the victim remains Artemisia who, after the rape, had consented to Tassi’s requests only because she was convinced that he would marry her.

A surreal trial in which the young woman is physically tortured by the Sibyl: her hands were tightened on ropes and pulled. Flathead screws squeezed her fingers and seriously injured her hands. With this dramatic torture Artemisia would have risked losing her fingers forever, incalculable damage for a painter of her stature. However, she wanted to see her rights recognized and, despite the pain, did not retract her deposition, replying “it’s true, it’s true”.

But her honor is lost forever: she is accused of incestuous relationships with her father, of having numerous lovers and inappropriate behavior. To turn his back on it is Tuzia who confirms all the slander with her testimony. Tassi is imprisoned for eight months, then accused of theft, debt, sodomy, incest with his sister-in-law and being the agent of the murder of his wife, who then miraculously escaped.

Shop some item inspired by Artemisia

FORCED TO MARRIAGE

After the trial, Artemisia was forced to leave Rome and marry a Florentine artist Pierantonio Stiattesi: a marriage to silence the gossips. There is also to say that Artemisia was a beautiful woman, and had many admirers. Because of his appearance, the scandal affair and the fact that he was independent, the malicious rumors about his conduct continued to circulate on his account throughout his life and even after.

Despite these turbulent events, Artemisia shows all her talent, she moves to Florence where, unlike her husband, she is welcomed at the Academy of Drawing Arts: she is the first woman to obtain this prestigious recognition. She obtained important commissions from the Florentine families (including the Medici) and became friends with Galileo Galilei, who had great esteem for her, and with Michelangelo Buonarroti the young man, who commissioned her a canvas to celebrate her illustrious ancestor and maintained a correspondence with her, which she acquits having recently learned to write.

In 1621 she went to Genoa for a short period, then returned to Rome as an independent woman, definitively moving away from her husband, and taking her daughter Palmira with her. In Rome, however, she did not find the job she was looking for: she was appreciated above all as a portrait painter and for her biblical heroines, but no one ever commissioned her from large frescoes or important altarpieces.

After Rome he is in Venice, and probably stays there between 1627 and 1630, looking for new commissions. Subsequently he lands in Naples where he finally obtains his first commission for a church, the cathedral of Pozzuoli, and there he remains permanently if a short English parenthesis is excluded in London, where he reaches his father to assist him until his death. This is the opportunity to collaborate artistically with him, after so many years away. In 1642, with the outbreak of the civil war, Artemisia left England and, after other movements of which little is known, she returned to Naples where she died in 1653.

THE FORTUNE

Artemisia’s fame is great among her contemporaries, even if her most recent fortune is perhaps more linked to the dramatic and romance aspects of her life, and to her courage in facing them, which have made her almost naturally an ante litteram feminist heroine. This reading, however, risks obscuring the strength with which Artemisia imposes herself as a painter, and on genres decidedly far from that “peinture de femme” on which other women (not many but not very few) had ventured up to that moment, limited to still lifes, landscapes, portraits – even with extraordinary inventions such as those of Sofonisba Anguissola. Artemisia tackles “high” painting: sacred and historical subjects, monumental systems; with a total mastery of painting, and completely embracing the Caravaggesque lesson, radical in the conception of the scene, in the contrast that describes the shapes and colors, in the preference for a close cut that dramatizes the relationship with the viewer, in the abandonment of conventional iconographic modules. As a confident art professional, she knows she can explore even more lyrical tones, more intimate atmospheres. The wide range of its strings is in full harmony with the baroque feel.

I'll be in control

of my existence``

THE HERITAGE

It is his own works that highlight the theme of the conflict both from a thematic and figurative point of view, both from a formal and poetic point of view, as can be seen well in his Giuditte, which do not skimp on concreteness or the characters he puts into play scenes, nor to the wounds they put in place. The rich series of self-portraits is equally eloquent, as are the nudes, which are not very idealized.

Some of her paintings are symbolic: in Susanna and the Vecchioni, there are those who see their father and his attacker, Tassi. In Giuditta and Holofernes, a work of great violence, there are those who read the woman’s desire for revenge against her rapist. Still, she read in his biblical heroines, often flanked by friends and maidservants, her disappointment at the betrayal of Tuzia who allowed the violence and accused her in court. However, it is rather reductive to consider his work only as a ransom or sublimation from the violence suffered, since in its completeness, it expresses a poetic power and variety that go beyond its biographical story.

Artemisia has been able to fight the prejudices of a male-dominated society to establish itself as the artistic excellence of its time. Although, like many other artists, she had to wait a long time to see her talent truly recognized and appreciated. What is certain is that she was an extraordinary painter, for her ability and for her courage to be a woman in control of her destiny, despite everything, in the seventeenth century.